Parks

Yulia LeonovaA park is the most nature-like and thus the most deceitfully natural artificial world. However, as well as the cities, parks are built artificially. The formula of a garden-city is simple, with nature and civilization in equal proportions. A park is a basic counter-figure to civilization, a place of retreat “into nature”. However, its greenery grows on the fruitful substrate of human culture. A garden is perceived as an aesthetic object; however, two essential stories of civilization are encrypted in its design – Functional and Ideal. At the same time, sooner or later every natural space – when fenced, tamed, and rearranged for some function – becomes a cultural concept: philosophical, social, scientific, but first of all metaphysical. An orchard becomes a Garden of Eden, and a Paradeisos as a hunting park becomes a Paradise.

A plan of an Islamic garden vividly illustrates this kind of an ascension from utility to the uppermost metaphysic character. Elementary irrigation unit, represented by the water source in the centre and two cross-axial channels, uniformly distributing water throughout four sunken panes with plants, have given life to one of the most beautiful and stable garden schemes and have become one of the most spiritually consistent spatial gestalts.

In the times of Achaemenid Pasargadae it was interpreted by means of the Zoroastrian division of the universe in four parts, four seasons, or four elements: water, wind, soil, and fire. Later, as a part of Islamic culture, metaphysics of a quadripartite garden got its most complete form. Perpendicular axes line off the hierotopy of a Christian monastery garden with four Eden rivers. In cultural systems with strictly fixed social and ethical arrangement a sacred garden space is programmed as the manifestation of the eternal truth. In case of evolving cultures, the new ideals are being delivered to the society through the newly created landscapes.

Limitless humble submission to the greatness of the Creator was replaced by the manifestation of power over nature. In Andalusian garden complexes, which in a formal and stylistic way reproduce in full the complexity of the Islamic metaphysics, the seeds of future obsession with power were already ripening. Roman irrigation techniques, skillfully developed by Muslims, and an extraordinary rise of agriculture brought pride of being a lord of the nature. Terraced position at the slopes of the mountains seduced with a ravishing feeling of a ruler, experiencing supremacy when observing a wide panorama of the imperial territories. Mirador became a command bridge of a Master. The ultimate expression of this was displayed in the Versailles manifestation of power, where a ray of Le Roi Soleil’ sight physically pierced an absolutistic artificial scenery from the Royal bedroom to the horizon.

Almost every artificial nature has a platform, arranged in a special way, for a visual and mental interaction with the developed world – a mirador of the Andalusian Caliph, Le Corbusier’s roof garden, a belvedere and a viewing mound in the Enghien park, ancient Chinese Lingtai – a divine stage to touch Heaven. These tremendous earth terraces served as the observation platforms for the emperors of the Shang dynasty emperors of the 2nd millennium BC in their enormous reservation parks. An emperor, standing on the Lingtai terrace between the Sky and the Earth, lines off the landscape in vertical direction and encircles a threefold structure of the universe in Chinese philosophy, San Cai: Heaven, Earth, and Human. In ancient Chinese version of the world order a human being is an equal part of the universe; he completes the heavenly order: enhances the natural character of things, puts them into tangible, symbolic form.

The outstanding scroll “Along the River During Qingming Festival”, some researches say, represents not actually a real Kaifeng, but an ideal city of the Song dynasty. In the multiple copies, made in different eras, a reproduction of one individual artefact always varies – an image of the garden palace in the left part of the scroll. The Qing Court Version represents the most extended garden palace, ably integrated in the artificial, or, to be more exact, artfully advanced nature.

The scroll has plenty of Gongshi images – the geological wonders known as “scholars’ rocks”, “ready-mades” of Song Dynasty postmodernism, both original and simulacrum objects, which regarded nature as an artist, whose work was an extended self-portrait in miniature. The finest rocks of unique shape with multiple holes were being taken out from the bottom of Taihu Lake, but few were aware that before this stonemasons had made holes in them and put them in the lake, letting time and water wash away the traces of the tool application. End versions of the stones were often set “upside down”, as if the stone was “flying and dancing like a cloud”, following the all-time favourite technique of the Chinese artificial landscaping – a game of imitation and metamorphoses.

The Chinese intellectual, admiring Nature, is being its co-author, who uses its basic elements as art mediums. (And when we are talking about Artificial Natures, we are talking about Artistic Natures as well.)

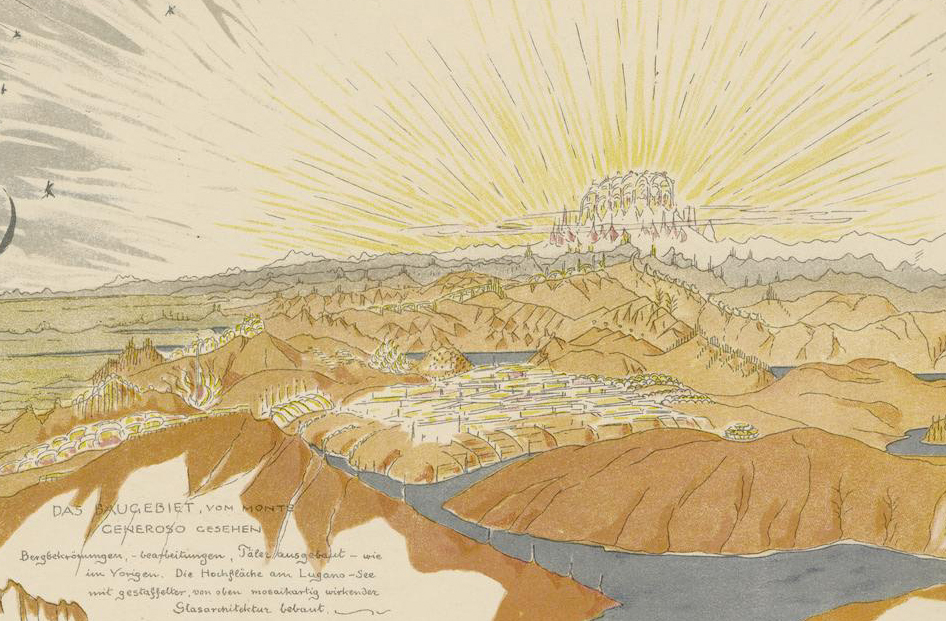

Mineral metamorphoses as land art mediums are no less rich material than vegetation. Each of the diverse cultures plays its own game with crystals. A range of interpretations is limitless – from Islamic metaphysical aesthetics to the megalomaniac project “Alpine Architektur”, built on the basis of spatial and architectural fantasies by Paul Scheerbart, Bruno Taut, Wenzel Hablik, and other members of Glaserne Kette.As Rosemarie Bletter said, their man-made crystalline accretions were a metaphor for the new man, who would live in a country without national borders.

Starting from the “faceting” of the Alps, Taut’s project ends with a chapter about Sternbau (Starbuilding). A head motif of his artistic utopia is to change society through the very process of changing nature. Despite a complete infeasibility of the creative fantasies of the Glaserne Kette members, a discourse on the glass architecture is incredibly fruitful. A sparkling kaleidoscope of Alpine Architektur repeatedly emerges in the manifests of Traut’s contemporaries and modern architects, creating spaces of transparency, purity, freedom,and openness. Consequently, one more basic element, the air, is included meaningly in the artist’s palette of the creators of new Artificial Natures.

On the other hand, the crystalline metaphor has not come out of nowhere – according to Blatter, Taut continued an iconographic theme, from stretches by King Solomon, Jewish and Arabic legends, medieval stories of the Holy Grail, through the mystical Rosicrucian and Symbolist tradition down to Expressionism.

In Islamic metaphysics crystals are only a part of an endless process of recombination of organic and non-organic forms of nature. In the interpretation of Titus Burckhardt, a Paradise is an eternal springtime, a garden perpetually in bloom, refreshed by living waters; it is also a final and incorruptible state like precious minerals, crystal and gold.

Animals are recombined into vegetation, vegetation is recombined into minerals, flowers – in stars, stars – in the deceitfully abstract geometry, geometry – into calligraphy, which grows back again with vegetative sprouts. At the same time the bionics of the Islamic architecture brings stones to life, puts Samarkand and Isfahan domes into organic shape, turns the arch columns of Mezquita de Córdoba (Córdoba Mosque) into palm plantation, mould Muqarnas “honeycomb” vaults of Al-Badi and Medinat Al-Zahra Palaces.

The sunken floating carpets of gardens, the flourishing mosaics and stucco of pavilions are meant to praise the Creator; and at the same time the resulting mesmerizingly ornamented spatial harmony again tempts its masters with pride for their created beauty. The magnetism of its radiance can even make it fully artificial, and then golden and silver trees with birds in cages appear in the gardens.

Ruggles tells, that in Madinat al-Zahra a large pool of mercury was placed in the center of the hall. When the sun was getting in, it sparkled with light, as slaves caused the mercury to vibrate. In the garden, al-Mansur ordered that pieces of silver and gold be inserted into the lilies, when they were still closed in the morning. In the afternoon, as the lilies opened to the sunlight, they were gathered on a tray and set before his guests, who were astounded to see that the flora of al-Andalus yielded silver seeds and golden pollen.

Mannerism, always ripening hidden within the great styles, filled the gardens of European baroque with the unusual shapes. Enghien park is full of fancy structures; its creators, like the Chinese, play with garden metaphors again, and the repertoire of the codes, encrypted in the scenery, is unparalleled in richness. Paradise allusions in the garden are now enhanced with the alchemical allegories, scenes from Greek mythology, and reminiscences to the Roman ruins. These plots are captivating and can be diversely interpreted. However, the more meaningful is the fact, that the artificial nature of Enghien, as well as the artificial nature of other neighbouring Dutch parks, evolved together with the ideas of their time.

Their complex plans demonstrated the rise of mapping, having reached the level of Art. Three-dimensional perspective panoramas of parks from a bird’s-eye view were implemented by the high-class engravers, such as, for example, Romeyn de Hooghe, an artist and a sculptor of the Royal gardens, the author of the album with the scheme and views of Enghien. Maps and plans were turning into wall decorations, and their independent visual value allows us to easily imagine, that the park was being designed just to look good on paper.

The patterns of fortification art were being drawn on the pl?ns and on the European terrain as well. By Prévôt, new military engineering technologies allowed the transfer of loads of soil, as the appearance of artillery weapons required the skill of digging trenches and building walls and ground defences fast. These technologies moved on to the garden building and were used during the construction of split-level terraces and slopes, channels, and pools. This was the time when boulevards were still military defences – bolwerken, and the rough beauty of star forts was included in the arsenal of park geoplastics. The grand pavilion in the centre of Enghien is surrounded by the bastions, and the military connotation shifts to courteous in mannerist way, reminding visitors of the fortress of love, which was a popular image at the time.

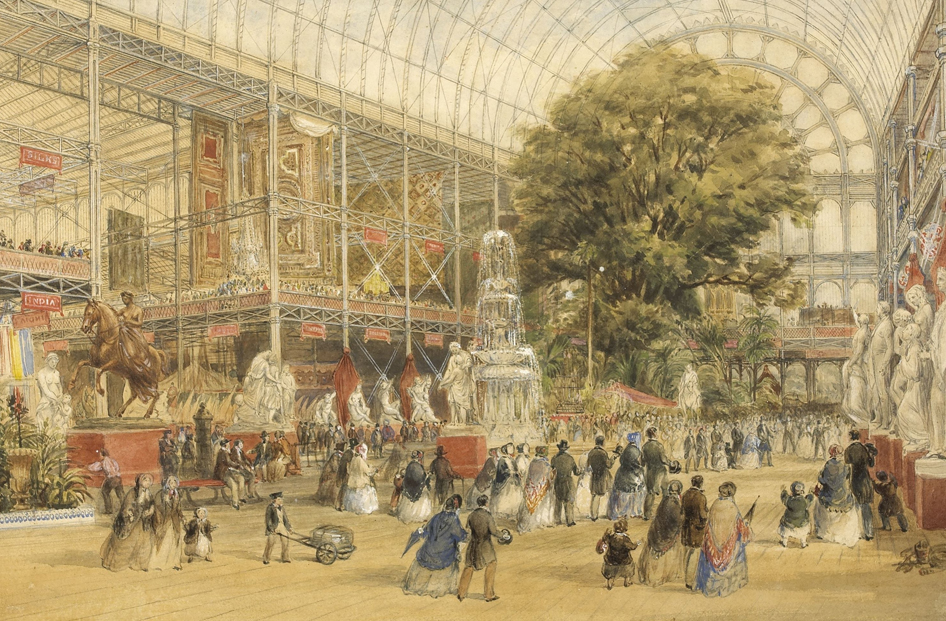

The orangery of Enghien is filled with exotic plants – colonial seizures, introduction of the new colours, a collection of fancy foreign things lead to the development of one more type of the artificial nature – Kunstkamera-garden. By the 19th century the orangery reached the size of Crystal Palace – a huge exhibition facility for tropical plants, artistic and scientific artifacts.

The design of Crystal Palace was inspired by the structure of a giant leaf of tropical Lily Victoria Regia, for the upkeep and display of which a horticulturist Joseph Paxton had designed a special pavillion. The exotic flower itself, along with the same combination with the glass architecture, later served as a source of inspiration for Taut and Sheerbart, who was especially impressed by the Dahlem orangeries. A little later young Roberto Burle Marx, having visited the glasshouse at Berlin-Dahlem Botanical Gardens, was struck by the richness of tropical Flora from his native Brazil, and that influenced his entire future career.

The size of the glass structures became so tremendous already in 19th century, that, as Schoenefeldt points out, one of their designers, John Claudius Loudon, jokingly offered to immerse an entire Russian village in its artificial climate. However, the ideas of Joseph Paxton, the author of Crystal Palace, indeed were aimed at the use of fully-glazed structures as the means to creating new types of environments for human beings in the scale of the population of large industrial cities. Proposing a glasshouse as a provider of artificial human habitats, he wrote, that there would be supplied the climate of Southern Italy, where multitudes might ride, walk, or recline amidst groves of fragrant trees, and [there] they might leisurely examine the works of Nature and Art, regardless of the biting east winds or the drifting snow.

Half a century later a wide glass arcade caIled the “Crystal Palace” was placed by Ebenezer Howard in the centre of his Garden City. A discourse of Paxton, who dreamt to secure favourable environment for the people to flourish, astonishingly precedes the theory of Patrick Geddes, the author of 1925 plan for garden-city Tel-Aviv. A biologist by training, Geddes considered the main task of urban planning as to make this and that town, as it were, a human garden of the world, where each form of life may grow and develop according to its nature.