The Garden City Of Tel Aviv

Yulia LeonovaThe idealized version of White Garden City of Tel Aviv, which miraculously blossomed on bare sands 100 years ago, is not so far from the real city as it may seem. The ideas of Tel Aviv’s visionaries, founders, and planners are integrated in the city’s scenery. An overview of the city plan, then zooming in here and there to a scale of a flower container on a balcony, reveals how its shape, street patterns, architecture, and greenery represents a visualization of the first new exemplary Hebrew city, aspirations of Garden City theorists, ideas and manifestos of the Modern Movement architects.

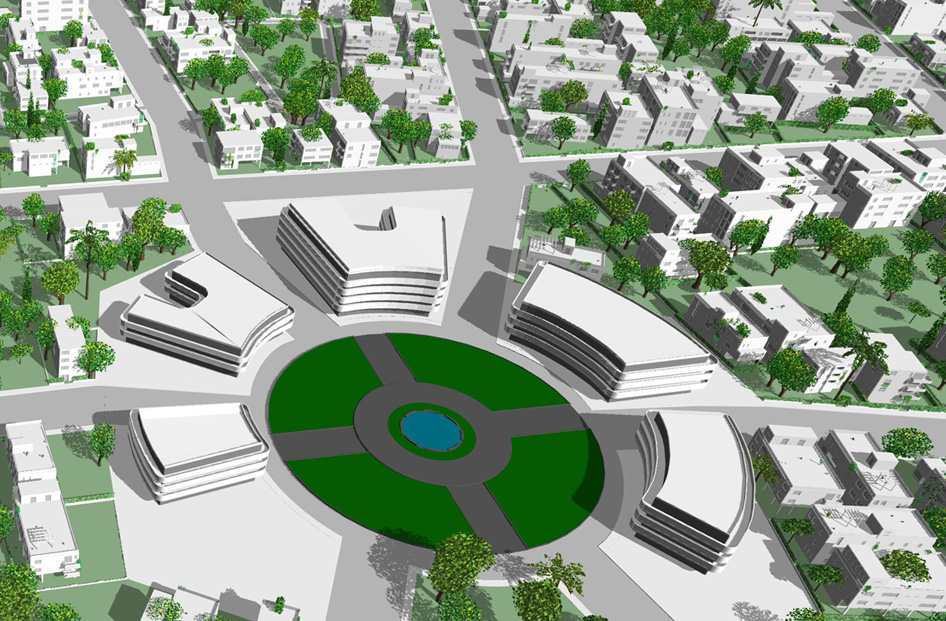

The layout of Tel Aviv’s historical part can be perceived as a half circle – this continues a series of round layouts of numerous Ideal Cities, beginning, for example, with the 8th century Baghdad, and finishing, for instance, with Howard’s conceptual scheme of a Garden City of tomorrow. The Green Belt idea by Loudon and Howard is easily traced in the shape of the chain of boulevards of Tel Aviv, which start from one of its first five little streets in 1909, and in Regional Plan 1948, where again the green belt was offered, now within Greater Tel Aviv as “a network of public open spaces lying round and within the town, parks, public gardens, paths, river banks and other green areas.” An ideal circle of buildings around the city’s legend – Dizengoff square – is in the orbit of the circle symbol as well. And Hug (the Circle) – was a name of an architectural association of young modernists in Tel Aviv in the 30s.

Primacy of the architecture of the 20th century – function – did not cancel the unchangeable inclination of the spacemakers to feel like being a Master of the Ideal Order planning. Beside pure pragmatics there was always a room for the aspiration to draw a Happy City, to program it to flourish by putting it into a right shape.

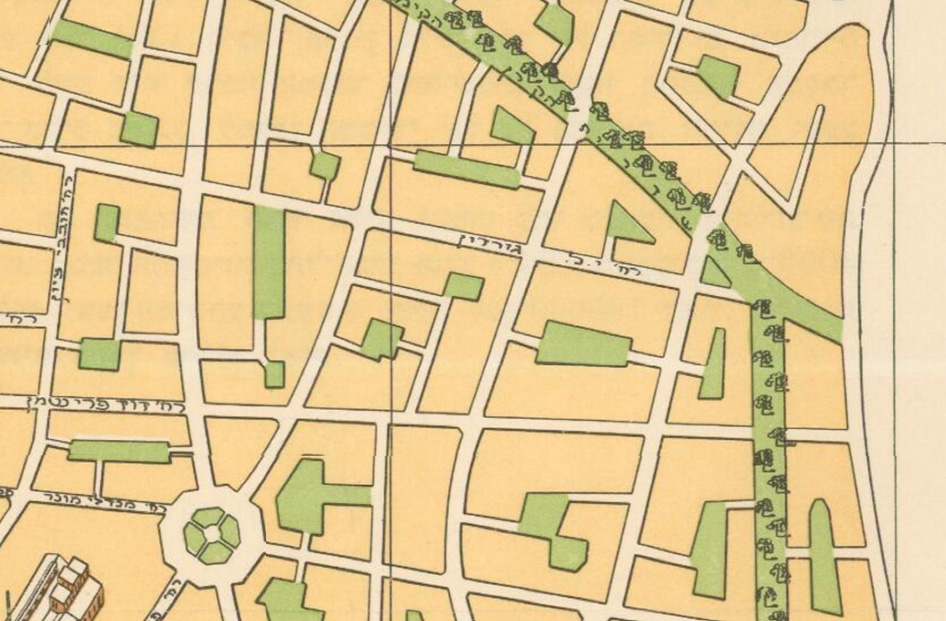

The most part of historic Tel Aviv was built under the 1925 plan by Patrick Geddes – he was as well inspired by the magic figures like for example hexagon, which he perceived as having metaphysical and bee symbols. However, it was not a regular shape he built his urban planning theory upon, but geographical and historical genius loci, sociality, and garden culture.

Geddes was an urbanist-biologist, sociologist, a follower of Thomas Henry Huxley; he was religious and scientific at the same time; he was full of love to human civilization; he called cities a drama in time, but he designed them as the most favourable areas for the living organisms: “to find the right places for each sort of people; places where they will really flourish. To give people in fact the same care that we give when transplanting flowers.” For him, the actual cities are the highly organized cultural and organic entities – Cities in evolution; each has its own faith, which left the trace on its landscape physiognomy.

When planning Tel Aviv ,Geddes drew new streets along the caravan paths and old vineyards. He always took great care of it, rejecting Haussmannism and standing up for the value of the pattern of the old streets of Paris, London, Boston – as they originally were the hunter’s clearings and cow-paths. (Had Le Corbusier known this expression, when he urged to lay absolutely straight streets in his City of tomorrow, calling winding ones Pack-Donkey’s Ways? He wrote then that some planners like Camillo Sitte has been made them into a religion, while a “modern city lives by the strait line: “We must have the courage to view the rectilinear cities of America with admiration.”

The real shape of historic Tel Aviv does not copy an ideal, universally applicable shape, having kept only an echo of the circular significs of Howard’s scheme. However, Geddes’ spatial scenario of a garden city is seen clearly – an organic grid lines off the city in dozens of communities: “Home Blocks”, neighbourhood clusters with inner gardens.

In that cellular system each cell should be an urban garden village, with a green open space for recreation, gardening, and communication, with a place for the accumulation of the community capital, as it can be called today.

Such were the Sunnyside Gardens in New York City and Garbatella in Rome – oases of artificial nature, surrounded by the houses, nostalgic for the receding vernacularity; however, unlike the experimental areas, Tel Aviv is a city. The city, which should have embodied Geddes’s favourite notion: Eutopia, a place, where no one feels Naturestarvation. “Eutopia lies in the city around us; and it must be planned and realised, here or nowhere, by us as its citizens each a citizen of both the actual and the ideal city seen increasingly as one.” His Home-Blocks system should have been “in no wise Utopian Dreams, but Utopian Facts – the very best sort of facts.” In his utopian Tel Aviv everyone was “to sit under one’s vine and fig tree”, while to convert this into reality is one of the very easiest and speediest of all biblical counsels of perfection. The city should have become not just a Garden City, but a “Fruit-Garden City – “Almond City” – Orchard City, Vine and Fig Tree City – Orange City and more.”

Le Corbusier pierced his pavillion Esprit Nouveau with a live tree at the exhibition in Paris in 1925, the same year that Geddes wrote his Tel Aviv Report, full of spirit of Victorian aesthetics.

By that time Tel Aviv architects of the Arts&Crafts generation were already feeling new trends; social ambitions of urban planners were drifting to socialism. Geddes’ home blocks were not destined to be build up by the houses of the invented style of Orientalized Hebrew historicism – it was replaced by modernism: international spirit, pure form, white color, and – a new green vision.

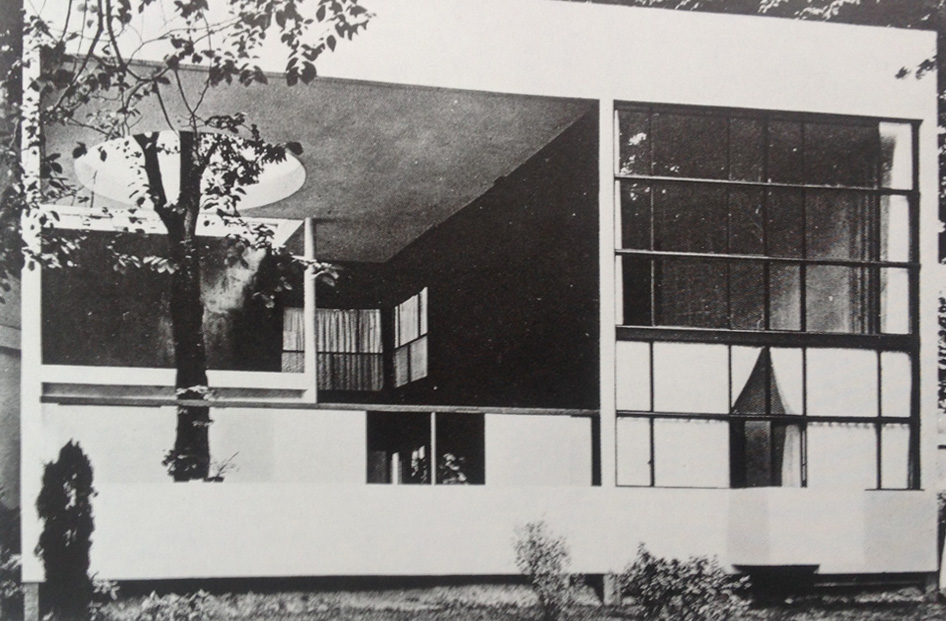

Gideon wrote that the task to break down the boundaries, which had traditionally existed between interior and exterior space, was a central concern of architectural Modernism. As Dammet points out, the early modernists Hermann Muthesius and Peter Behrens, both involved in Hellerau’s planning, placed great emphasis on the importance of gardens in the new architecture: “a garden could facilitate the spiritual renewal, that many others in the early twentieth-century avant-garde were seeking. According to Le Corbusier, the future city above all must keep in view the aim of taking man back to nature.” His three environmental principles of modern architecture have become a new vernacular of Tel Aviv: piloti instead of the ground floor; flat roof for gardens; ribbon glazing, transformed into ribbon balconies.

The modernists designed Tel Aviv as Gesamtkunstwerk in the spirit of the Bauhaus manifestos. A private villa, an apartment building, a power station, a gas station, a park, a kiosk, a promenade now spoke one architectural language. Students and followers of Muthesius, Fisher, Migge contributed to the influence of the German version of the garden city. All together it was meant to become a single architectural and landscape environment.

Fences, benches, flower containers were not just a set of the arranged objects; on the contrary, they continued the building, which was organically growing into the scenery: architectural benches and balcony flower beds – as structural parts of its architecture; fences and fountains – as modernist sculptures in the garden.

White cubes of houses on earth pedestals with flower terraces were merging into their old new land: were putting down roots. Fully glazed lobby performed a spectacular play of shades of green on the translucent leaves to the person, intending to leave the house; and the garden under the pilotis diffused the glaring light on entering a sunny, noisy street.

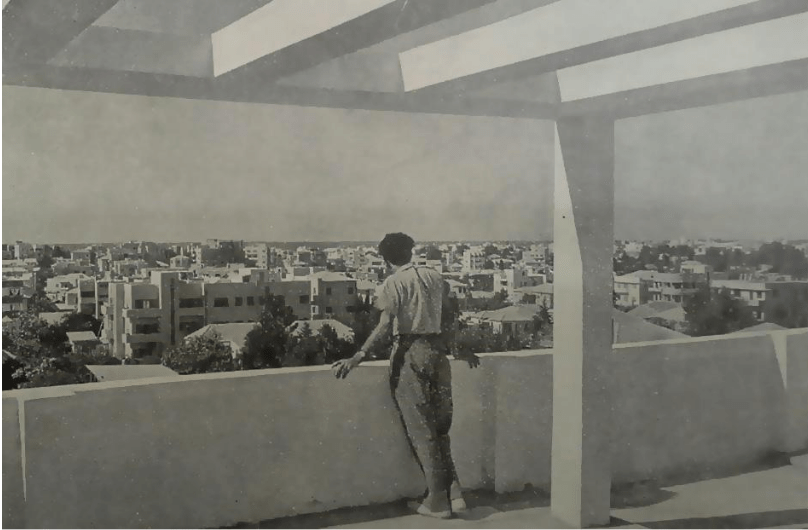

The green balconies, surrounding a house, functioned as a climate shell, which eased the Levantine heat. A roof garden was aimed to top the House-Garden system; to be small green Eldorado on the roof for plants and people by Leberecht Migge, and the essential culmination of the architectural promenade by Le Corbusier. As Dammet wrote, “he placed the roof gardens and libraries next to each other, as if to state their equivalence as clearly as possible, since Le Corbusier saw the promenade both as a way of paying homage to the natural world and as an induction into a meaningful encounter with nature.”

In reality Tel Aviv roof gardens were scarcely implemented – most of the time the idea of it was denoted only by its synecdoche – a massive concrete pergola. Having lost its utility as the supporter for plants, the concrete pergolas gained sacral meaning for the White City of Tel Aviv, which is easy to track on the iconic photographs of the chronicles of its construction.

Every time a desire to overview the territory under formation was typical of its creator – a conqueror, a monarch, an artist, a colonizer, a progressor. The most remarkable Artificial Natures appeared there and when the society faced something significant. One culture had a task to fixate the eternal values, and the other – to develop new ones. That is how Ideal Garden City of Tel Aviv was built.

… And that was the way Roberto Burle Marx created his Artificial Natures of Brazil, and a new nation was coded in these landscapes.