Research general

Our group concentrates on the general topics of ideal spaces and related, on that of artificial natures. At a first glance, both these notions seem a bit exotic if not purely academic, to say the least. But they aren’t. Particularly our Western culture dealt with both of them since long, in theoretical as well as practical terms, and entire worlds had been created taking them as guidelines; again, too in quite practical terms by moulding our concrete environments we recently are living.

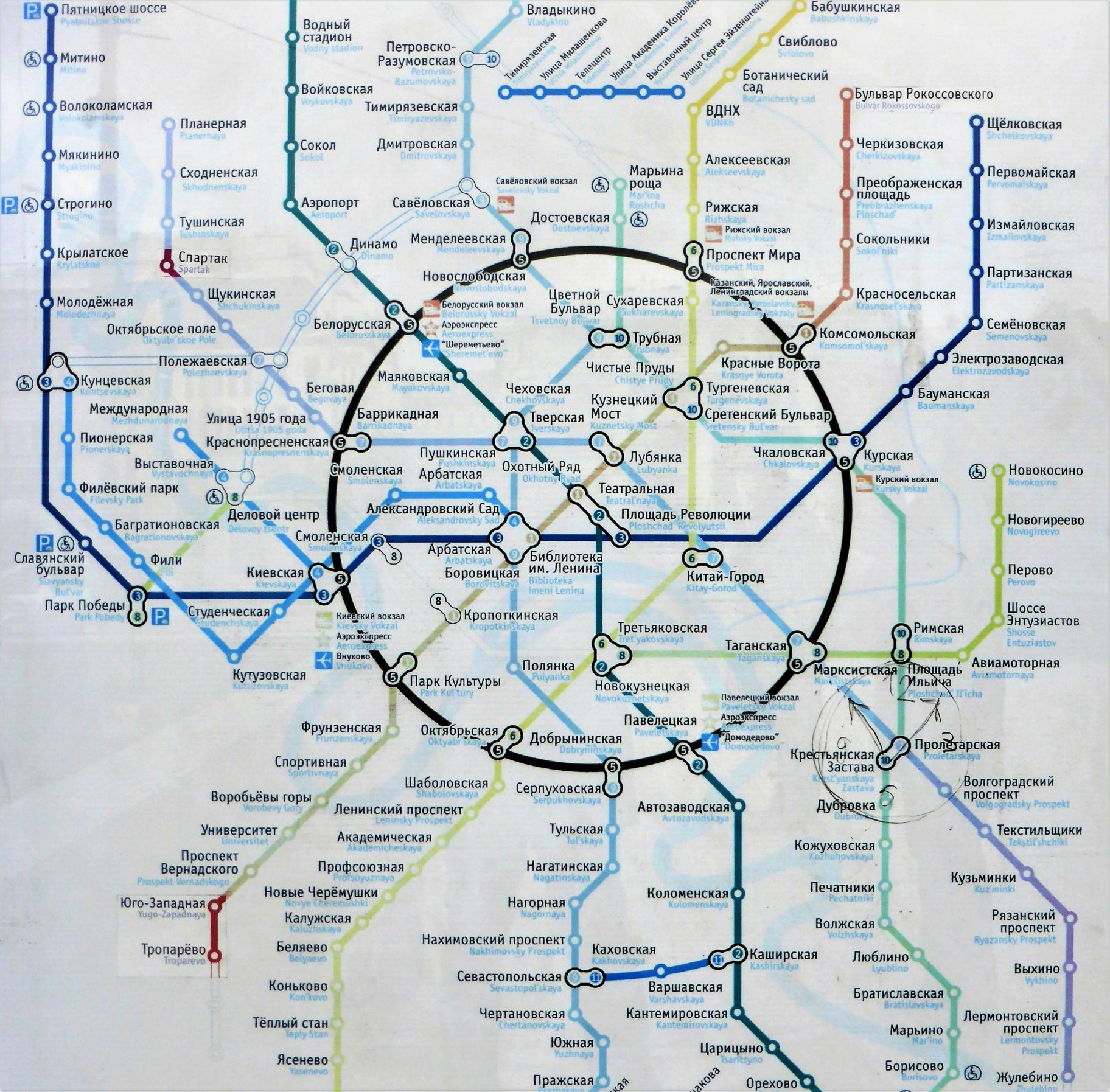

An ideal space is a space that on the one hand, is a space imagined (from the Greek eidos, and idea); it is a space we conceive and plan, putting it into real life then. Modernity for instance is full of such spaces, from early infrastructural networks to recent digital spaces.

On the other hand, an ideal space is a space perfected, a one laid down according to optimized rules, ranging from ideal cities, ideal states and other classical utopias to recent approaches to construct new ‘ideal’ spaces for new communities based on the Internet. The classical trope of the ideal space is utopia, the desire for erecting an environment where humans can live together in new ways, for realizing their positive potentials and by that, to become “really human”. One can easily see that when discussing about ideal spaces we inevitably tackle another topic, that of an (assumed) human condition, or conditio humana. And related, the whole history of ideas referring to both, the ‘ideal’ space to be constructed and the ‘human condition’ it shall serve for.

The notion of an artificial nature too has a long history, inside the general terms of understanding and world conception of our Western culture. That is expanding worldwide since about 200 years, influencing the other cultural spheres which existed before as autochthonous entities. The idea of an artificial nature strongly relates to that of an ideal space, first and foremost in a utopian dimension. A natural environment is a one that is (a), common for human beings to live in – it became ‘natural’ since it became the ‘normal’ environment for them, on a daily basis; and (b), it is conceived as an environment that is suited for human beings. From the idea’s beginning, the basic hope was to create such an environment for humans that is more ‘natural’ than (original) nature can ever be. It started with the classical concept of the garden or park, the altera natura of Cicero, and evolved rapidly in modern times, from garden cities to Internet communities.

Aligned to an artificial nature are myths of a primarily monotheist, Christian heritage – the paradise, first of all, but also the hope for redemption and the myth of a fundamental dichotomy between nature and culture. These mythic ideas appeared in disguised forms of manifold appearances since the era of Enlightenment, and very urging again in the era of Modernity. In postmodern and recent times, they underwent a revival under the aegis of postmodernist modernization and its related concepts like actor-network theory, part-time utopias of the most diverse kinds, and the like. And, combined with a prominent myth of the New Age up to now, that of a makeable world – the conviction that we are able to create our own natural environment, preferably as a second paradise – the ideas about an artificial nature found their most prominent mythos: the one of management. According to a myth of a makeable world, it is the belief that everything can be managed, i.e. transformed into an artificial nature, from infrastructure to entire ecosystems.

Probably since the onset of civilization as a sedentary way of life, but for sure since Modernity we all live in managed spaces, irrespective if we know about that or not. Particularly in the utopian discussion, the topic of management has been grossly underestimated. Such spaces became our real artificial nature, and at the same time, as do the other types of spaces outlined here, they reveal a lot about our basic conceptions and the assumptions underlying them. To turn the world into a bad place is a question of management – to make it to a better place also. Inter alias, management is a technique, a set of means to achieve something. And related to the topic of a conditio humana, the question is what has to be achieved, and why. In large parts, in particular under recent conditions of a so-called neoliberal world, management might be an issue of technique – but it also rests in convictions, basic assumptions, a cultural memory. It rests in values, in one word, and these values, made explicit or existing just as an unthought known, determine what is managed in which ways. Therefore, we cannot speak about spaces without speaking of management: the attempt to develop, maintain and control an artificial order. Which is neither the order of nature nor that of a ‘natural’ behaviour of human beings. But an order made, planned according to some guidelines. And creating a truly second or ‘artificial’ nature as an embracing environment for humans, from early Sumerian city states to Internet networks.

At least for human spaces, the notion of space relates to the one of morphology, or gestalt. When speaking about space, no matter the kind, we speak about the conception of entities which are wholes, gestalten, and not just some agglomerations of fragments or singular elements. The modern very idea of a system already refers to it, as does the one of a network (that superseded the ‘system’ as a culturally valid lead metaphor). Gestalt relates to the perception of spaces (also to ideal ones achieved and maintained by management), and we can change the spaces we live in only if we first fully perceive and comprehend them, as space. Out of this, the issue of immersive environments became a crucial one in our research, next to the histories of ideas leading to all those spaces outlined so far. But gestalt is not confined to static structures. Also processes can be expressed as gestalt, i.e. in terms of a morphology. Morphology is more than just a pattern. It might be that every gestalt is a pattern, too, but not every pattern is a gestalt. For instance, the virtually endless pattern of a ribbon is just a pattern, it lacks gestalt in the true sense: a confinement, also in spatial terms. To express processes as gestalten, to compare their morphologies with the aim of managing them better could become a very fruitful research area. To understand complexity in new ways of epistemology.

© 2016 Ulrich Gehmann All Rights Reserved