Terrace World

Ulrich Gehmann, Yulia LeonovaThis world is an idea. And like any utopia, it could be located anywhere. But it is, as was the world before it, the Centre Mondial, a concrete utopia. It could be located in Europe, for instance, to be set up in formerly abandoned rural areas to be revitalized, or in arid regions to be developed for human settlement. Its flexible overall structure and basic mode of organization allow for manifold adaptations to differing conditions. It could be located in plains (as it is here), on mountain sides, in hilly woodlands – wherever. It can even actively change its shape, according to conditions of population growth.

And it consequently centres on the topic of community and place. Which is the prime point of importance for this idea. Let’s have a look at it. As said, it is an idea for community life, for new forms of it.

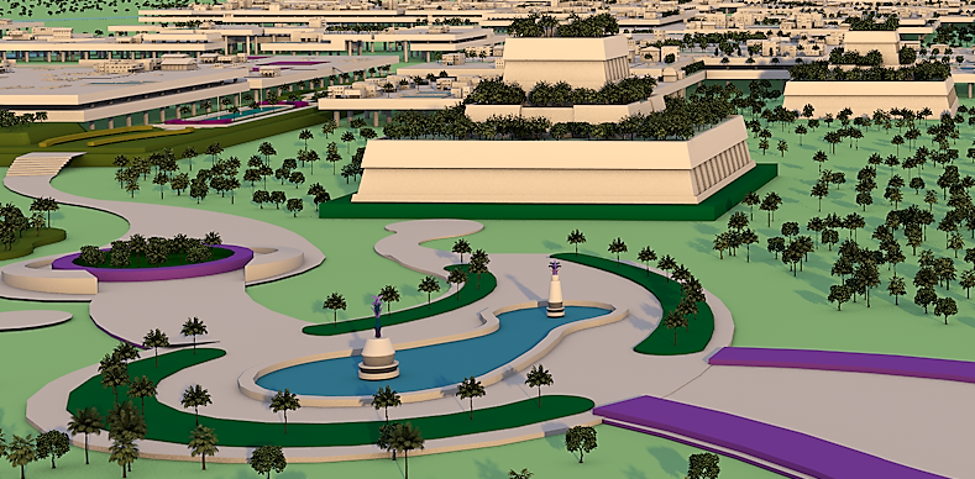

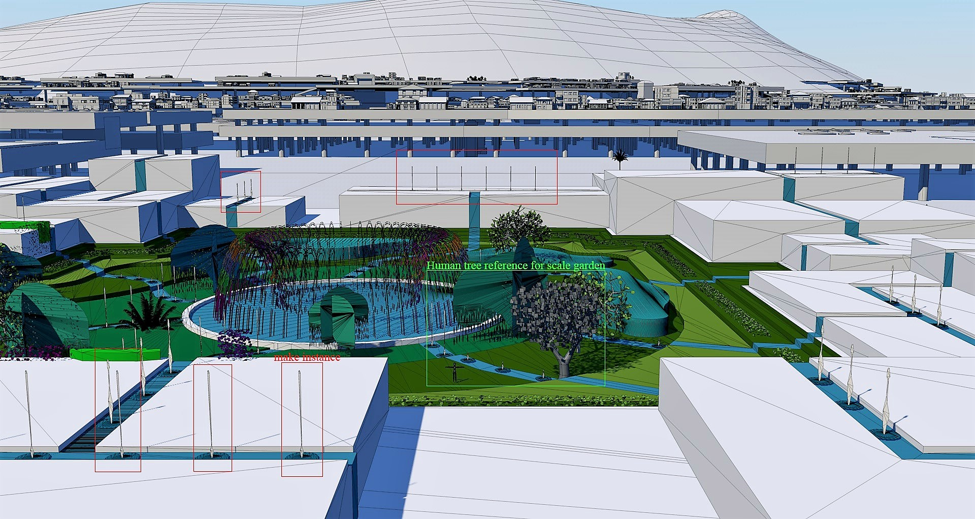

We see one entrance to this world, with a park in the foreground stretching out (on the upper left) into the settlement area, the Art Garden. That world’s basic structure is simple: Next to intermittent pyramids and ground floor-areas, we have two levels of terraces of different sizes. To be populated by communities and/or to be used for urban agriculture and gardening, even for smaller parks – as the community in question wants to have it. In its total, it is a flexible, non-symmetrical organic structure allowing for adaptations: in case of population growth, idle terraces can be inhabited or new ones erected; in case of a diminishing overall population, terraces can be left idle or transferred to other uses than housing, e.g. as areas for urban agriculture, or for making a park if two or more neighbouring communities unite in such a venture. It depends on overall population development and first of all to community decisions what is done, and what not. Here, we see the entire structure in more detail:

By approaching the settlement, we realize all in all three levels of terrain: the ground level, presented in the foreground as an idle space with trees; the two levels of terraces for habitation, agriculture and gardening; and the pyramid-like buildings placed intermittently into this entire structure. At the far right, we see parts of the settlement up to grow the nearby mountain slope.

In the pyramids, central organizational functions are located, for keeping the settlement’s overall administration and management support. Also, additional housing facilities can be placed there. These centralized functions are needed but have to be restricted to a minimum. There is also a kind of parliament, made up by elected members of all communities, to decide on issues that all communities will affect. The parliament meets at certain time intervals in one of the pyramids.

The settlement

The supply infrastructure is running on the ground level, beneath the earth; and inside some of the piloti-like columns of the terraces, for delivering the different communities with water, electricity and other supplies needed. Other columns serve for waste water and different kinds of garbage. The main function of these columns is to support the terraces, for saving settlement space. Imagine the total surface covered if all these communities would be located only on the ground level. Through the terrace-system, even larger population densities can be sustained on a comparable smaller overall surface.

The transport infrastructure is running on the ground level (not shown in our model), and each of the terraces is assisted by several elevators. There is no car traffic, not even on the ground level. You have to park outside and use the public transport facilities: railway, and a metro system running underground.

Here we see a part of the entire structure from above, with the different levels and two gardens (both to come), the “Geometrical Garden” on the left, and the “Water Garden” on the right. In the lower part of the image, in the foreground, a part of a large agricultural field is visible. Different terraces on the same level can be reached by bridges (upper left), terraces on different heights are connected via ramps and stairs (lower right). Theoretically, a visitor or a member of a community interested in the different cultures of the other communities could walk through the entire settlement, visiting them.

Each of the terraces provides light slits for the areas below that are covered by a terrace. To ensure that also in regions which have no direct light of day some natural illumination is guaranteed, next to the artificial electric light.

Under the terraces, storage-, repair- and production-facilities are located since nobody houses there, and plants do not grow. Production sites in need of full light of day are placed outside the settlement, as well as recycling facilities and waste dumps are. But the majority of the materials needed by each community are located right under its surface, under the respective terrace or terraces – in case a community extends over more than one terrace. Which is possible and matter of debate between neighbouring communities. In addition, communities can unite in common projects, e.g. planting a common park which can be used then by all the participating neighbours.

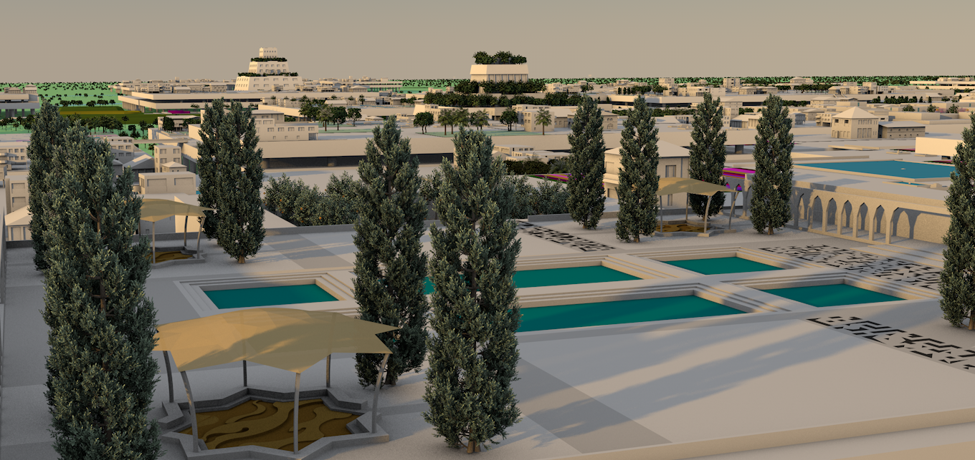

A section of such a common park is shown here, the Geometrical Garden overlooking the terrace world. Imagine you could stay there under one of the tents, discussing with friends and neighbours; or put your feet in one of the water basins on a hot day. Such experiences and qualities of life can be multiplied a thousand times, inside and outside your community.

The basic idea underlying the whole settlement is to maximize decentralization, to foster diversity via different communal developments. The respective communities living on the terraces, their places, have their own rights of managing themselves and for the design of their terraces. For such a design, they get the requested materials free of charge – materials for the buildings, plants and seeds to start, earth needed for making gardens, etc. The coordination of these material flows, as well as those of energy and water needs, is managed centrally for the whole settlement but follows on request of the communities. Aside from essential basic supply functions (like electricity, or water) provided constantly for all communities, the single community has to bargain and to agree with the central managers what is needed for which purposes, and in which quantities and times.

All the rest – how to design their terraces, what to build, what to plant – is entirely up to the community in question. The community decides upon in which place it wants to live, and how it wants to live. So, over time different community cultures will evolve, each one with a maximum degree of autarky, and autonomy. Also as regards self-sustainability. You cannot buy Gucci shoes in such a world (except from the outside, or imported by traders), but each community has its own gardens, often with some small husbandry, to ensure its own living. Over time, trade between communities evolves, exchanging goods and ideas.

Finally, we have a look at the outside world.

The Gardens

In the following, a series of gardens will be presented, as exemplary cases of how such a world can be enriched by manifold different structures and places.

The Art Garden

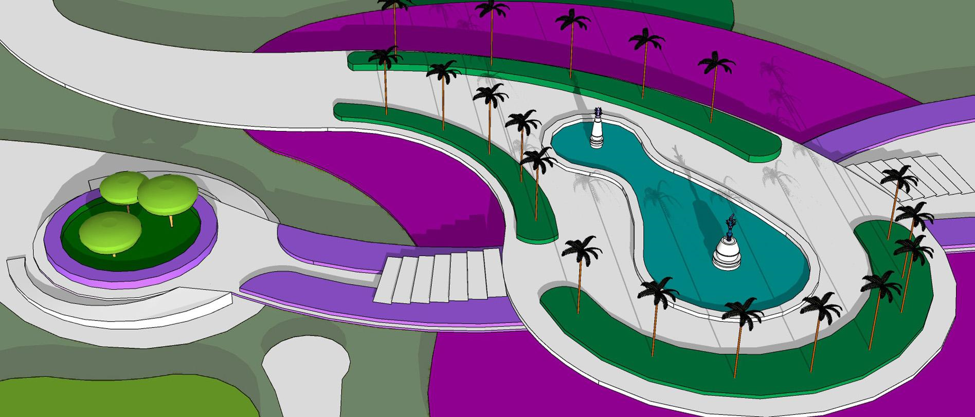

That garden serves as a park for all the inhabitants, connecting different terrace’ communities and promoting creativity. Like an homage to Roberto Burle-Marx approach, it is designed like a giant abstract picture. The main style and structure are already arranged, but the park has yet enough space for festivals, performances, art and flower shows. The long promenade and sophisticated multi-levelled structure of the splash-formed main area of the Art Garden provide all the freedom for dynamic and spatial ideas of participating artists.

The Geometrical Garden

The garden is inspired by Islamic garden and ornamental art, with its richest knowledge of mathematics and outstanding masterly design based on it. The Garden’ landscaping is playing with digital matrix theme, both aesthetically and technologically. Smart tents react to the level of insulation and weather, “digital” pavement to temperature and light, sandboxes are “laboratories” for AR games. A great tradition of geometric design was transformed into a future shape.

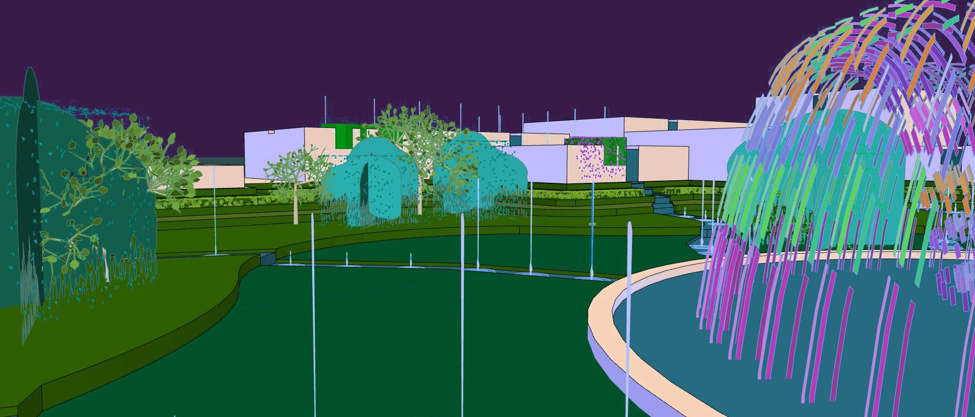

Water Garden

Water canals constitute a network that connects a compact and close-knit community. The inhabitants are open and friendly, enjoying the communal Water Garden in the middle of the compound. Water, the main image (Gestalt?) of this garden, like Geometry in the previous one, plays two roles, acting as a landscaping and information medium. Water decorates and feeds the garden, and, at the same time the dance of Central Fountain reflects what is going on in the virtual activity of the community.

For revealing the human scale, the garden is shown from its inside, with a look at the diverse water fountains. The fountains in the central circle can be illuminated at night.

Geddens Garden

This type of garden could be ideally for a community on the Terrace World. Geddes Garden is the exemplary element of Garden City idea by Patrick Geddes, the original planner of Tel Aviv, Israel (see our exhibition Artificial Natures).

It is an ideal model of the neighbourhood which balances between private and communal values. Each house stands on its own plot with its own garden, but all of them surround the public garden. Its landscaping is diversified depending on people needs, it has places for urban vegetable gardening, playground and ornamental plants. These plants of the pocket garden, and other trees, lawns, hedges and climbers grow everywhere, greening all the cluster due to the whole system of its architectural and spatial design, – its plots, lanes, green gates, containers, balconies and flat roofs

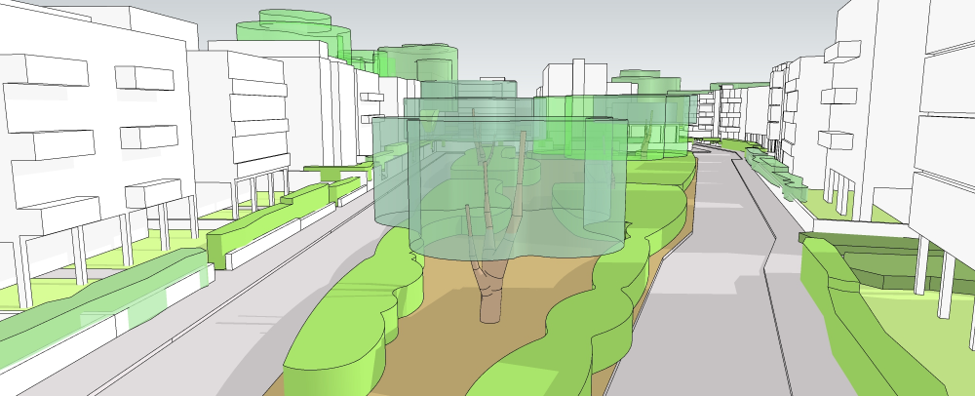

Urban Agriculture

Areas reserved for agriculture and larger-scaled horticulture (for seeds, fruits, young plants) are scattered throughout te area of the Terrace World, to ensure its population with the nutriments and crops needed. Their dispersal ensures easy local accessibility and avoids the ecological dangers inherent to large monocultural fields. These areas can be changed from time to time, giving way to other forms of use; above that, not being agriculturally used all the time helps the soils to regenerate. Below we see on the right such an agricultural field inside the city fabric, on the lower left an abandoned area with wild trees.