The Heavenly City and Paradise

The Heavenly City and Paradise

A project for the World Assembly of Churches, August 31 – September 08 2022, city of Karlsruhe/Germany, in the cities’ main church, the evangelische Stadtkirche am Marktplatz

Ulrich Gehmann

Image layout by Faranak Tiba

Edited by Flora Loughridge

Introduction: Notes on Paradise

A heavenly city is not really about the city but is about paradise. “Paradise” can take many forms. Traditionally, it can be a city, a garden, or a combination of both, and the idea of a paradise, as an inner image, is connected with religious belief. But one does not necessarily have to be religious in a traditional sense to long for paradise. Paradise can also be a utopia destined to be built by human effort alone, or a paradisiacal natural state of existence, which we hope to reach again.

There are some common traits inherent to the notion of paradise, irrespective of its form. First and foremost, it is a space that is ideal in the sense that it is both imagined and perfected: perfected because there is no other place that can be conceived as being more perfect than paradise; imagined because paradise does not exist in the present moment, but is something expected to come. Paradise is associated with the future, even in the case where an original paradise once existed but was subsequently lost. It has to be regained, in order to be achieved once again in the future.

Secondly, with a view to future perfection, a paradise embodies an end state in time, a final state that cannot be surpassed. No matter its form, whether religious, utopian, or needing to be regained, the world and history as we know it ends with the advent of paradise. Once paradise arrives, both the world and history will be completely different to what came before. Strictly speaking, history ceases because a perfect end state always has the same history – it is free from upheaval, sudden changes, suffering and evil. History as we know it turned into one of the ever same, into a history of the perfect. If history equates to evolution or development, such a state of being can no longer be considered history, since an end state, whether religious or not, cannot evolve any further; it is an endpoint.

Thirdly, in relation to this, a paradise is a state of universal peace and harmony; conflict and the possibility of evil cease to exist. Paradise is associated with the re-establishment of cosmic order and harmony. The dangers of evil disruption are banned. We are redeemed when we reach paradise, freed from history, conflict and evil. In that sense, we could live forever.

For those who long for paradise, the belief in paradise, whether secularized or not, is a myth, a holy and therefore true tale, rather than being just a story. Like any true tale, paradise tells us who we are and where we go, about the meaning of history and hence, of human life.

In the case of our Judeo-Christian heritage, we have progressed from a primordial paradise that was our original state of Being at the beginning of history, towards the end of that history, namely a second and final paradise at the proverbial end of all days. History gained meaning, and became more than just the accumulation of changes and chance. It became defined as progress, and had a destination. Life gained meaning.

The myth was alive even after it became secularized, taking the shape of earthly utopias destined to be built up, of scientific, technological and social progress, of going back to nature. Progress, so the myth tells us, is liberation and redemption from material confinements of every kind, even from human nature as it is now, with all its biological constraints.

The Beginning: Original Paradise

There have been many attempts in history to locate and to imagine the original paradise, the natural state of existence where humans lived and from which they departed after the onset of civilization. This assumed primordial state of human life became an abstraction, a remote glimpse of a situation when people (still) lived in harmony with our surrounding natural world and with ourselves. According to this myth, this way of existence is equal to the original and genuine human condition. If humans were truly human, they would live life simply, as depicted in monotheist sources, in images of the noble savage, or as evidenced by modern anthropological findings.

When embedded within a religious context, paradise is to be described as the Garden of Eden, a mythical space that is located in multiple ‘concrete’ places. When considered from a secularized perspective, such as one developed during the Enlightenment era and which still survives in the scientific anthropology of today, paradise could be any- and everywhere: it exists in any space where people find harmony with themselves and with nature.

According to our Judaeo-Christian heritage, in the original version of paradise, there were two trees of central importance, the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge. Eating the latter tree’s fruit led to expulsion, as we know from the tale of Adam and Eve. However, the Tree of Life remained as a symbol of hope and longing: that one day, people would come closer to paradise, to a natural state of living, rather than remaining completely caught up in the entanglements of civilization, with its technological dependencies, problems, crises and shortfalls.

The Fall

The original paradise was lost. The fall from paradise into civilization caused humans to become alienated from a primordial state of genuine harmony. According to modern anthropology, this dynamic separation has been occurring ever since the onset of a sedentary lifestyle. It is also evident in the Bible: the cursed and sedentary Kain was the founder of the first city, and his descendant Tubalkain became the master of technique: a human capability that is directly opposed to nature.

Being civilized ended up a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it made great achievements possible: the creation of cities, architecture, art, craftsmanship and technological progress. On the other hand, a path of dependency developed, which caused humans to gradually adopt a de-naturalized lifestyle: the permanent division of labor, fixed social hierarchies accompanied by social inequality, the accumulation of wealth in the hands of only a few, crowding, ecological breakdowns, nutrition shortages and warfare, are all signs of this way of life.

The original, natural forest was replaced by a forest of modern-day urban agglomerations; for a large part of the human population, an artificial environment became our new ‘natural’ surroundings.

The Hope

According to Mc Clung in The Architecture of Paradise, paradise “is a strange land but a familiar presence; few have been there, but many people have an idea of what it is like.” Nevertheless, or precisely because of that, the hope of reaching a state of harmony, epitomized by paradise, has remained. 1

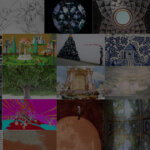

In the picture above, there are the two trees of original paradise, the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge, and a type of garden pavilion that symbolizes human presence. Interestingly, the architecture of paradise depicted here is no longer the natural state that the myth describes but an artificial paradise shaped by human hands, the “other nature” (altera natura) of the garden as the derivative of a primordial paradise. This is reflected in the word ‘paradise’ itself, which originates from the Persian pairidaeza, denoting an enclosure or park. It suggests an active effort to build up, develop or form something.

But even the primordial paradise, the Garden of Eden, was not ‘natural’ in a strict sense. In terms of our Judaeo-Christian heritage, it was an artificial nature from the very beginning, an artifact made by God. It was not generated by nature’s unplanned, self-organizing power but by an act of will.

According to this heritage, humanity is destined to strive from the first ideal space in its history, the primordial paradise, towards a second and final paradise, which is similarly an artifact made by God: the Heavenly City, Heavenly Jerusalem or City of God as the final ideal space for the redeemed. Irrespective of the form it later adopted (as a garden, city or garden city), following humankind’s expulsion into civilization, the path of human history developed from one artifact in the beginning to another at the end. Such a conception of history was a mythic image that influenced utopian constructions and concepts of redemption via progress.

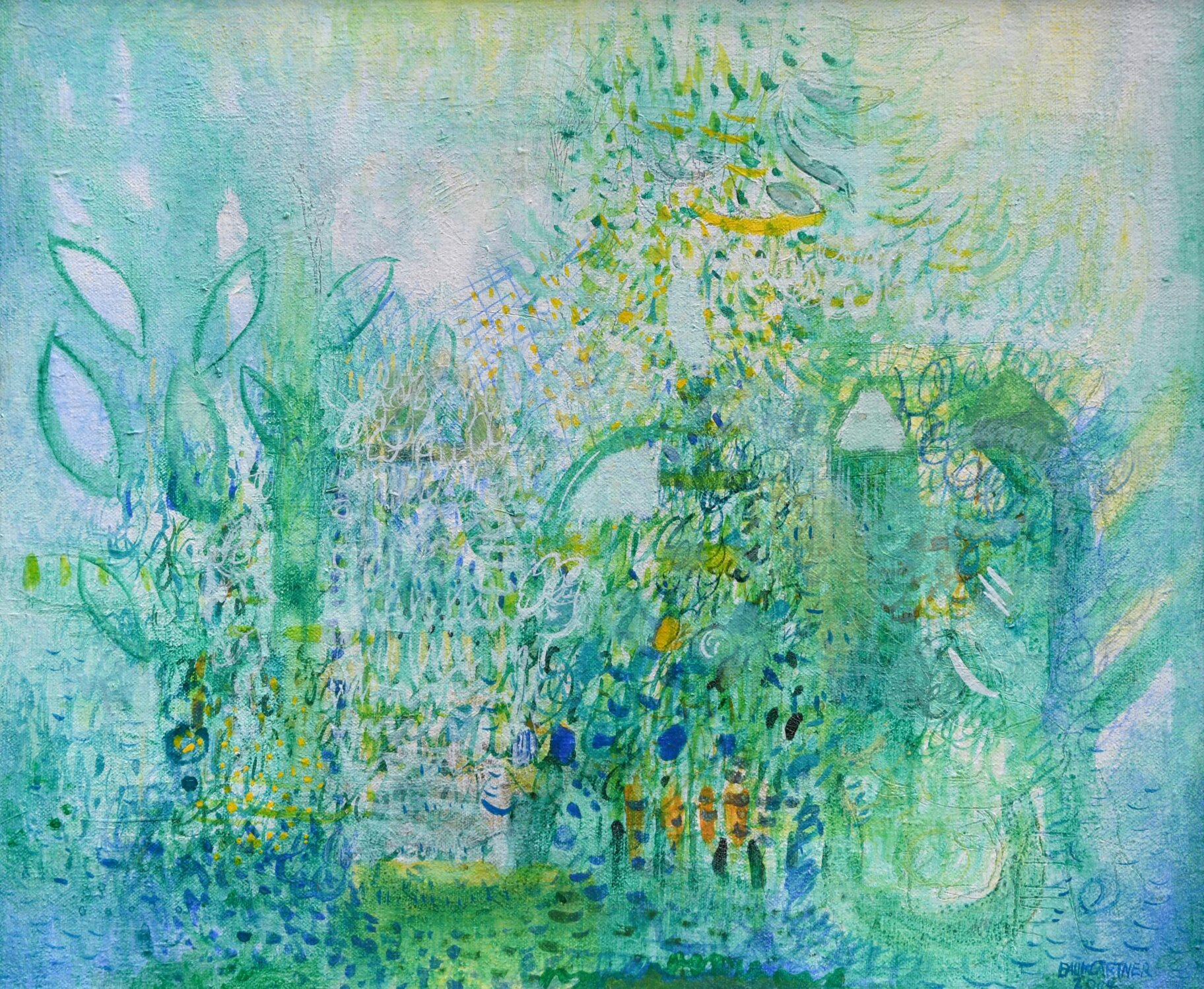

The Byzantine version of paradise portrayed above incorporates the Garden of Eden with the fountain of life and four rivers of paradise, a symbolic cosmic circle separated from the rest of the world, as indicated by the rocks outside the garden wall. The Heavenly City appears in the distance, promising salvation through detachment from earthly things. The hope to reach a final, paradisiacal end state remained, even when its sceneries became secularized, and the original religious eschatology turned into a new religion, namely into the quest for utopia. A compendium of Utopian Thought in the Western World states that “paradise in its Judaeo-Christian forms has to be accepted as the deepest archaeological layer of Western utopia, active in the unconscious of large segments of the population […] testimony to the enduring power of religious belief to keep alive the strange longing for a state of man that once has been and will be again.”

The idea of paradise is not confined to Western culture, or to Christianity; other cultures have developed their own views of and ideas about paradise. However, with the exception of Islam, no culture has ever been quite so preoccupied with paradise as the Occidental world. The central mythic hope is to achieve liberation through redemption, by once again achieving the ideal space of paradise.

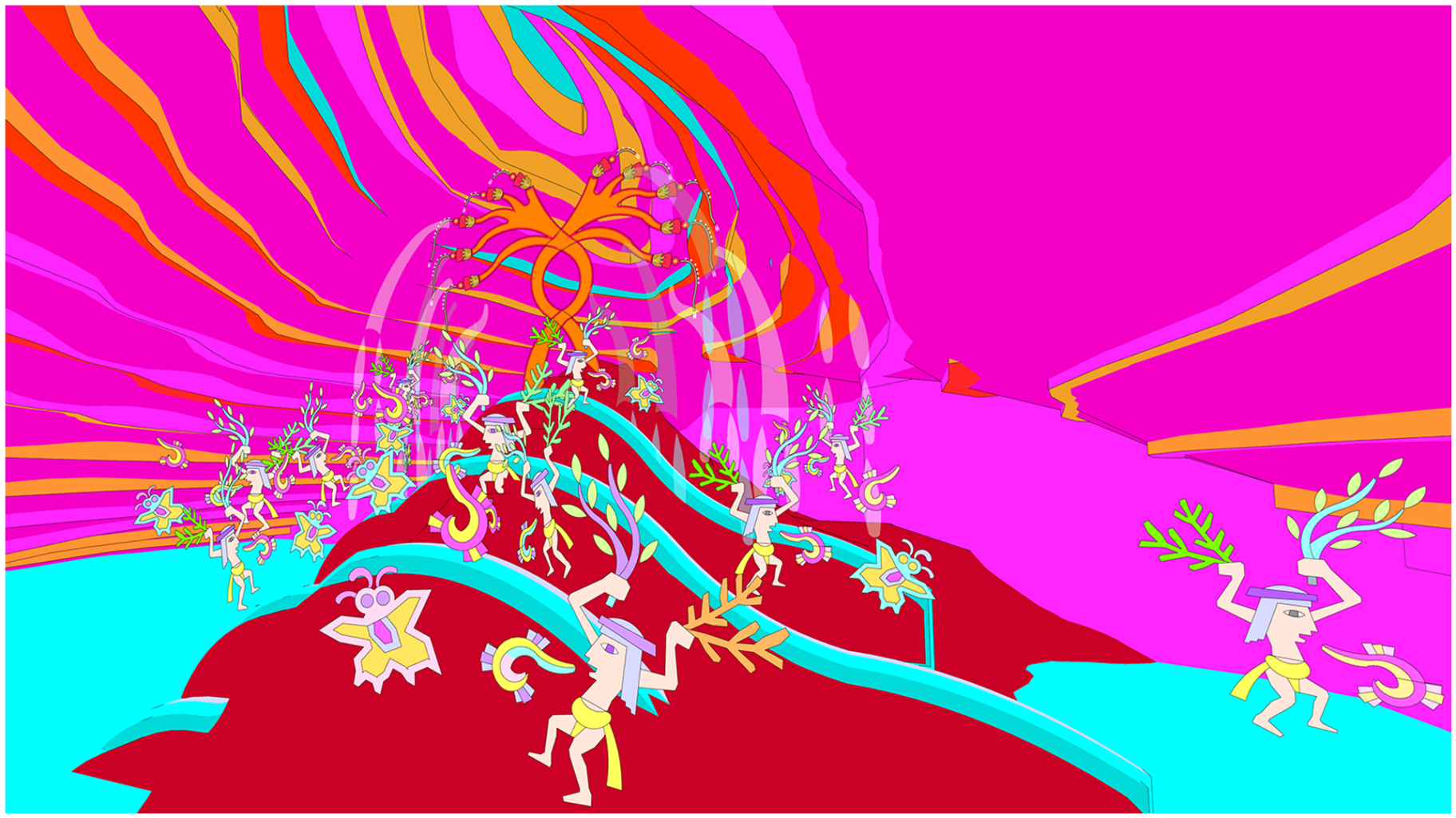

There were also concepts quite unfamiliar to us. This Mesoamerican version of paradise for instance, which is reminiscent of the first civilizations in the region, gives an indication of just how different paradise can be to different cultures. The image depicts paradise as an ideal space that takes the form of an enormous cave where the blessed are to live after death.

This image depicts Tlalocan, the otherworldly paradise and home of the rain god Tlaloc, a place associated with plenty of pleasant weather, and well-being. It is located in a large cave inside the Tamoanchan hill, a world mountain that is the mythological locus of the creation of gods and humankind. Paradise and world mountains unite to form a cosmic unity of a higher order. The Tree of Life at the top of the hill symbolizes the dualism and mutual dependency between life and death.

Despite the many variants and cultures defined by the origins of paradise, hope remained. And for those gifted people, it became possible to imagine the end of history, and visualize what was to come.

A dream unfolds and vanishes, only to unfold again another time, or in another society or culture. In the drawing of the sculptor Romolo Del Deo, the dream becomes apparent in its imaginative qualities, which are tangible, and presents something within reach.

Del Deo writes: “The experience of watching Creature Celeste appear stands at the intersection of contemporary and traditional ways of interacting with art in ecclesiastical settings. The animation reproduces the effect in compressed time, from the methods of Renaissance masters, of witnessing a Disegno Cartone or master drawing transferred to the ceiling of the basilica in preparation for the creation of a fresco. Instead of using a spiked wheel to roll over the drawing so pinhole guides can be transferred to the ceiling, as old masters did; we use high-resolution projection to mimic the effect that a 16th-century visitor to the church might have witnessed.”

The aspiration of the Creature Celeste, he says, “is transporting the modern viewer into a virtual space, shared with a potential viewer from centuries before, across time and culture. Meeting in an apparition upon a ceiling, a heavenly city, populated by heavenly creatures, an apparition of shared experience in a space that exists only in our perception but also is shared memory. A part of our past moving alive in our present. Pointing to our future.”

The End of History

The promise is to reach the end of history as we know it and to enter another world, free from the constraints and misery we previously had to bear. It is ultimately a mythical promise, regardless of whether it was formulated in the conventional religious terms depicted in the above image, or transformed into a secular utopian goal: to reach paradise not in the next, but in the current world. In both versions of this promise, it is about an outopos, a non-place; because such a place does not exist in the Here and Now, but has to be achieved in a future moment.

The Latin sentence at the top of the door, which reads tempus non erit amplius translates as “there will be no time left”.

Above the door is the snake-like Ouroboros, which symbolizes the cosmic connection between beginning and end. Death, symbolized by an old man lying on the right-hand side of the steps, appears to have lost his power. But the door itself remains closed; to open it, one must first find the key. The promise of paradise is within reach, yet also remote. Like a guiding star, it provides hope and direction, but the promise stays concealed within an abstract, written form.

The Heavenly City

The second paradise at the end of history is epitomized by the ideal artifact of the Heavenly or Celestial City, City of God, or Heavenly Jerusalem. It represents an image-paradigm (Andrew Simsky), a culturally inherited inner image of the paradigmatic, quintessential character. Although such paradigms can be symbolically presented in pictorials, they are ultimately non-pictorial, “mental images of the sacred” (Simsky) – just like the myth of paradise and the Heavenly City.

There are many different versions, interpretations and representations of the Heavenly City which exist in various times, spaces and societies. The following images exemplify the wide array of possible interpretations of the Heavenly City:

In the above image, a city takes shape in the distance, a version of fantasy becoming visible like a promise. Its unearthly character is similar to the ideal spaces of El Dorado; or the Heavenly City itself. These imagined spaces either stand indistinctly in the distance, in both space and time, or they become clear, even as an abstract version of the city.

The image above shows a section of what could be a Heavenly City; the city is not depicted as a concrete entity but only as an abstract frame. Even the light is cold and abstract. According to St. John’s Revelation, the City of God was not illuminated by the natural light of the sun and moon but only by God Himself. This kind of abstract frame could be filled with all imaginable (non-evil) expressions of its inhabitants; as, for instance, expressed in the image below.

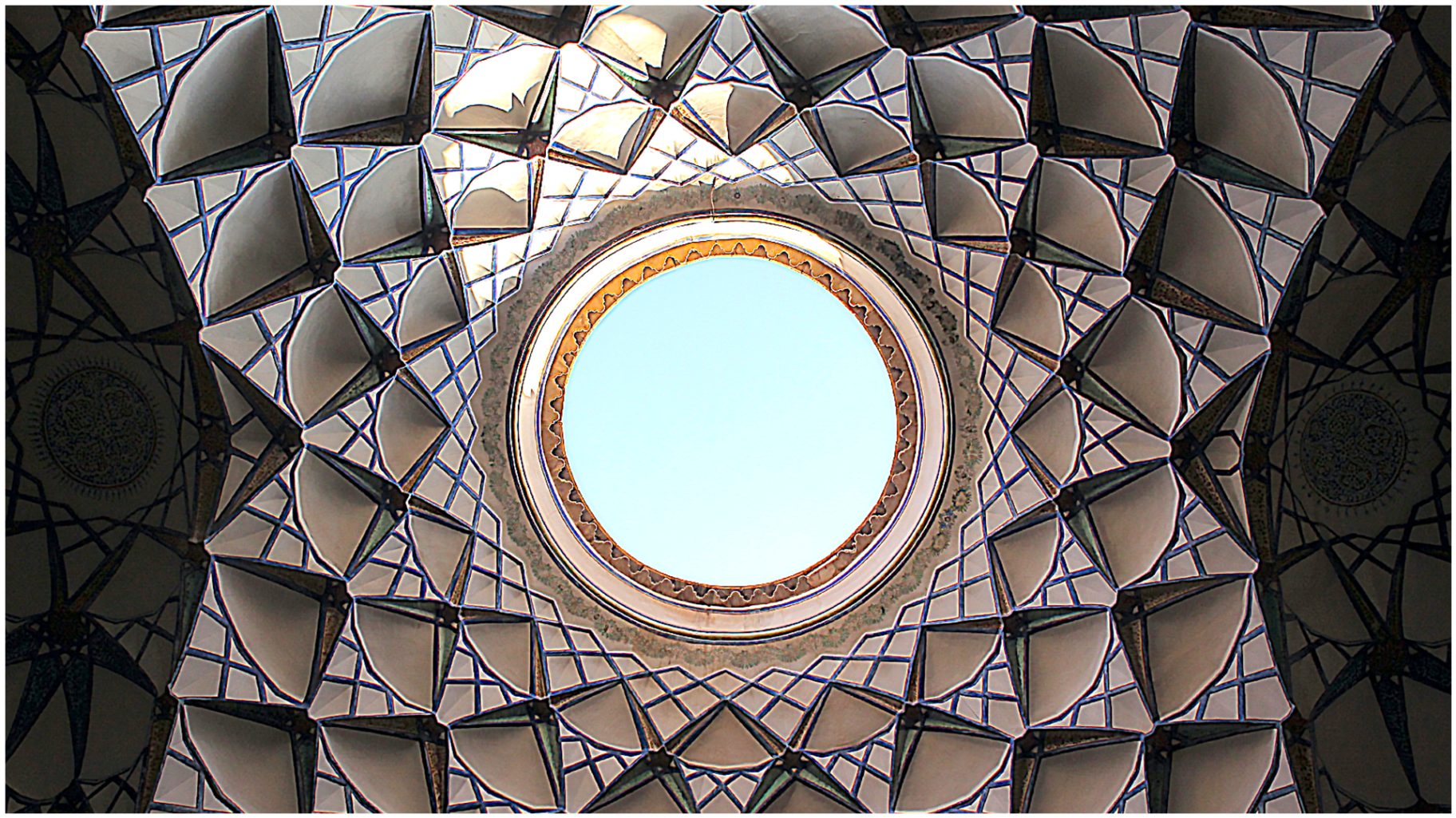

The Heavenly City could even be considered a collage of impressions, arranged as an architectural form. This is evident in the image below, a work of art that presents the ascent to the Celestial City in an upward-oriented dynamic that evolves from the cupola of a gypsy tomb.

The Gothic Cathedral

If the epitome of a second paradise is the Heavenly City, then the epitome of this city is the cathedral; at least here on earth, and according to the Christian roots of occidental culture.

The cathedral is symbolic in literal terms: here on earth, it is the representative of the Heavenly City to come. The materialized cathedral here on earth is made of “inert stones” but references the final one to come, a Heavenly City of “living stones” that is not bound to matter. It is an immaterial city that is real nevertheless, illuminated by the light of God, the New Jerusalem or City of God, as described in The Revelation. For the church father St. Augustine, the City of God was a construct that “transcended time and space, rather than a city built of brick and mortar” (A. Madanipour). It is indeed an eschatological ideal space ruled by divine law, the final topos for the redeemed after history has ended, the perfect end state for an ideal community. In its secularized versions, it became the intention of the utopias to follow after.

As an architecture of inert stones, it is a concept expressed most clearly in the Gothic cathedral. Reaching towards the sky, it becomes most apparent in the cathedral’s interior. A diaphane space opens up, a space that does not seem to be made of solid walls but which is translucent and transcendent, a space of light and transformation.

The Gothic cathedral, according to George Duby, is geometry woven in light. Based on the concept of Dionysios Aeropagita which talks of the unity of the universe, God is Light. God, pure Being beyond all Being, manifests as light. It is a spiritual light from which everything was created, shared in by all creatures and all material, in different levels of intensity, flowing from top to down like in a cascaded fountain, from the angels to the stones.

The architects who designed the Gothic cathedral believed that the language of creation was mathematical, and God was conceived as elegans architectus, an elegant architect who moulded the world with the help of mathematics and geometry. Numbers, said St. Augustine, are the thoughts of God. For Alain de Lille, a scholar in the times of the Gothic cathedral, God (and hence, the world) is the measure, number, and weight, encoded in nature; and the task of humans is now to decrypt the code, he says. One could hear modern science speak centuries before its actual appearance.

This is all reflected in the architecture of the cathedral. The form counts, not the individual content. The form follows the logic of fractal geometry, making a system of invisible vectors, which is a precursor to a cybernetic system. Moreover, as in the case of cyberspace which followed later, the architecture of the cathedral was essentially a system of immaterial dynamics, not of material, inert stones. It is therefore of little wonder that in line with Christian cultural heritage, Internet pioneers such as Howard Rheingold explicitly compared cyberspace with Heavenly Jerusalem.

This city, being the final place of the redeemed, is symbolically expressed by the cathedral, just as cyberspace stands for a machine utopia. The cathedral, according to Ed Finn, “is a pervasive metaphor here because it offers an ordering logic, a superstructure or ontology for how we organize meaning in our lives. A cathedral is a space for collective belief, a structure that embodies a framework of understandings about the world, some visible and some not.” The original cathedral, already mathematical in structure, has been superseded by a cathedral of computation (Ian Bogost), which rules our today’s world. The epitome of the new cathedral is software. Software, says Ed Finn, is like “a cathedral of computation, a powerful metaphor for everything we believe is invisible yet generates visible effects. Like the crucifix, the software is ubiquitous and mysterious even when it is obvious, manifesting in familiar forms that are only symbolic representations…” 2

This principle of representation already occurred in the old cathedral, i.e. was present ever since the beginning of these “superstructures”. Examples include the apsis of the cathedral, where the altar is located, which was always directed towards the East, the location of the first paradise; the arms of the crucifix, which are also reflected in the overall layout of the cathedral, symbolized the paradises’ four rivers; the West of the cathedral with its main rose (a cosmic symbol composed of fractal elements) symbolized the end of the world. Down to the smallest detail, the visible architecture was symbolic of another, more important architecture, that of an encompassing cosmic structure, an invisible world of meaning, all contained within the cathedral, a meta-symbol of the Heavenly City expressed as a total work of art.

The cathedral took the meaning of the symbolic to a new level, by taking the believer to a new level of reality (Sedlmayr) – just as the new cathedral of computation did.

New Worlds (Skopein)

We can now open up the sky. Century-long attempts to imagine a new paradise were possible after the arrival of the new cathedral, with ways of imagining that had never been experienced before. It is reflected in the Greek word skopein, which is also the working title of this project. Skopein does not just mean “seeing”, but also infers looking around and watching closely, investigating, or becoming aware of something, realizing the natural form of the seen; also, as a result, the process of considering and taking care of something.

This is all part of the experience of looking at the Heavenly City, also in the metaphysical sense. It is not only about the physics of what we see with our eyes. Since in terms of earthly space and time, the Heavenly City is essentially space- and timeless. There are other dimensions, pertaining to both space and time, which apply to this type of ideal space. As once symbolized by the rose of the Gothic cathedral, that space might still be a cosmos but is one beyond human comprehension, a multidimensional world order.

The animation New Worlds/Skopein, made by members of our Ideal Spaces Working Group Michael Johansson and Andreas Sieß, raises the mathematics already applied in the Gothic cathedral to a new level. The animation follows procedural mathematics that generates its own forms, which are expressed in a sequence of images. The Heavenly City/Paradise is presented as auto-evolving entities, which are, unlike their traditional precursors, no longer pre-given and fixed.

According to Michael Johansson, “the animation creates a unique audience experience in which animation and its unfoldings become a vehicle for the visitors’ own curiosity and imagination. The display, which draws from historical references, paintings, films, and other sources, encourages the audience to explore and reflect upon ideas and beliefs about what is up in space (all our scenarios are projected onto the vaulted ceiling in the city of Karlsruhe’s city church). “Gravity, imagination, and grace have been a key part of this sequence of images and our exploration of how an upwards motion into a projected space can be designed and experienced”, he says.

Having an upward-oriented viewpoint as in the Gothic cathedral, emerging auto-generative forms, spaces, and colors add richness and variety. “A complex and kaleidoscopic space is generated”, says Johansson, a space “in which visitors can independently explore and experience their own imagined versions of heaven.”

It had been said about the world order symbolically expressed in the Gothic cathedral that only angels were capable of creating myriads of crystalline configurations in immeasurable complexity and beauty (L. Spuybroek). And all these configurations were components of God’s world machine or machina mundi. Nowadays, it can also be generated by the new cathedral of computation.

A New Machina Mundi (Michael Johansson/Andreas Sieß)

Visitors are able to explore and experience these myriads independently. If redemption is the ultimate liberation, then it is about the individual’s ultimate liberation in this case. There is a shift in perspective, away from traditional conceptions of a Heavenly City, or final paradise. Irrespective of their differences, traditional conceptions about paradise had one thing in common: they were communal in a literal sense, places for communities. The new worlds presented here do not necessarily rely on the presence or formation of a community. Instead, they offer a multiverse of perception and imagination for the single person, the individuum, to explore; whether or not the individual belongs to a community is of secondary importance.

Real Utopia (Sharanam)

Returning to the concept of community and its ideal spaces: one alternative to longing for paradise is to choose not to wait for it, but to make a version of paradise by human means, here and now on earth. At the beginning of the 20th century, an era dominated by political and architectural utopias alike, Piet Mondrian, one of the pioneers of modernist art and architecture, said that “with some good will, it must be possible to create earthly paradises”. If paradise equates to some kind of utopia, it should be aligned with a concept German thinkers called konkrete Utopie, a ‘concrete’ or ‘real’ utopia: the ou-topos, the former non- or nowhere-place, was thought of as a concrete location, transformed into a real place for real people – no matter whether paradisiacal or not.

One could go one step further and conclude that people no longer even need to actively strive for paradise or utopia. Instead, it might be sufficient to build an environment suited for a human life deserving the name, and that this is a sufficient ‘paradise’; the more so when the future inhabitants of such a place are actively participating in its construction.

One key example is Sharanam, a completed project by architect Jateen Lad in southern India, where local people built a community building from the ground up. 3

The initial conditions were anything but paradisiacal. At the start of the project, the area near Pondicherry was an ecological disaster zone. There was poverty, unemployment, mafia, alcohol abuse and violence – almost the worst-case scenario when starting a project like this; a real dystopia, and a non-place without the prospect of a decent life. On top of that, the region had recently been hit by a tsunami, with devastating effects comparable to a biblical flood.

It was perhaps precisely for these reasons that the Sharanam project could start: as a venture to build something new, and good.

The local people were trained to construct the Sharanam buildings, acquiring new skills during the project that they had perhaps never dreamed of acquiring. The lives of those who participated in this process changed completely. According to Lad, the outcomes of the project were decisive: the project led to self-esteem, encouraged new-found respect of villagers towards one another and the environment, and an awareness of what had been really constructed here: a space made by the people, for the people.

Sharanam was not only about constructing a building. Just like old and new cathedrals, it also had a metaphysical meaning, by transcending pure matter and giving form to something new. Lad describes it as a “process of constructing a timeless, transcendental space using the primordial elements of earth and light.”

A symbolic building evolved an ideal space. Lad:

One celestial vault

Projected onto another

Earth onto concrete

Lightness onto mass

Mud onto sky

Lad expresses the project in the following sequence of images, inspired by the poem Savitri by Sri Aurobindo. Savitri is a goddess (a cosmic force), she is the shining one, who urges people to act.

Epilogue

1 More on this you find in the remarks on paradise by Alessandro Scafi from the Warburg Institute, presented in our Ideal Spaces’ workshop in the Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2021,Community & Concepts of Resilience – Ideal Spaces, topic 2, at 1:31: 35

2 More on this is in our , Interview with Ed Finn: Algorithms, Imagination and Reality – Ideal Spaces

3 More information on the Sharanam project, which was presented as part of Ideal Spaces’ one-day workshop at the Venice Biennale 2021, can be found on the Ideal Spaces website: Community & Concepts of Resilience – Ideal Spaces. (topic 3, 02.33), as well as Episode 9 of the Ideal Spaces Podcast, a conversation with Jateen Lad.

Ideal Spaces: Ulrich Gehmann, Faranak Tiba, Andreas Sieß, Michael Johansson, Emöke Bada, Yulia Leonova, Matthias Bühler

Guests: Jateen Lad, Romolo Del Deo, Nico Wollenschläger, Dieter Baumgärtner, Cyrill Oberhänsli